I go alone to an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean without shoes, or plans, even forgetting to bring swim shorts.

Whisked into French Polynesia under cover of darkness I ventured out from the airport at first light and saw a stunning landscape of sea and sky and lush forest. Right away I took a ferry across the channel to Moorea, a small and beautiful island of volcanic crags and coral beaches, and wandered off along the shore. Wisps of cloud drifted among the mountaintops, waves crashed on the reef, and the air smelled of flowers and salt and warm earth. I thumbed a ride half-way around the island, found a hotel, got a room, and stayed a week. I paddled a canoe out into the bay and peered through transparent turquoise water to coral and white sand below. I dove with schools of colorful fish, sat on the beach and devoured fresh fruit and coconuts pulled from nearby trees, and cycled past orchards and pastures and quiet villages. Some days I hid from the burning sun and read books, watched squalls blow in from the sea, or sat by the water each evening at sunset, talking with other visitors from the States, Australia, and Europe. There was no work to be done and nowhere to go beyond the edge of the island. Beautiful women abounded, dressed to varying extents in colorful pareos. Restaurants served fine French food and the happy Tahitians saw to it that alcohol was readily available for evening merrymaking. There were few insects and rain was infrequent. But wait - don't pack your travel bag just yet! Just days into your stay you may well find yourself as I was - indifferent and rather bored, cut off from the world and any of its scales by which one might measure success and advancement. The idyllic setting had melted away, and I was trapped on an island.

Some years on I'm willing to put forth a postulate grown from this trip and a good many others like it: Contentment comes not from having fine things, but rather from being able to get them should the desire arise. Comparably few things can be had on a small rocky island separated from the continents by thousands of miles of deep blue ocean patrolled by tropical thunderstorms. People who stay must soon cast off their ambitions, wanting little and doing less, else they will be driven by the emptiness of the place to build a sailboat and depart for distant lands.

Traffic was thick on the 110 freeway as it always is at rush hour. Sean left me at the airport with plenty of time to spare but I went first to the United terminal, stood in line for a long while, and was told that even though I had a United ticket I would check in with Air New Zealand. An hour before boarding I hurried through dark concrete alleys to the opposite terminal and was relieved to see no line at the check-in counter. "Are you checking bags?" asked the girl at the counter. I had none; in fact, all I had was a small shoulder bag scarcely larger than a laptop computer. I was soon on my way to security where they insisted on x-raying my plastic flip flops. Farther on at the gate I heard that the flight crew was stuck in traffic; I need not have hurried or worried. Instead I paced about and wished I'd brought a book. At a change booth I exchanged a small amount of currency and admired the large bills. Polynesian franks, each frank worth a US penny, were so big they didn't fit completely in my wallet. I felt rich until I realized that the funds would probably only last me 2 days of food and lodging. Tahiti is an expensive place, but at least in my small bag I had everything else I needed ...except my swim shorts! What a silly thing to forget. I wondered how hard it would be to find a respectable pair of shorts in Papeete.

Air New Zealand has not forgotten old standards of service: I ate from glass and china with metal utensils, not flimsy plastic like on other airlines. The stewardess was coming by with drinks: "Would you like a drink?" "What red wine do you have?" "Kin stah and mirla." I smiled, unable to understand her thick New Zealand Accent. "Yes," I answered. She looked at me, a confused and slightly irritated expression on her face. Somehow I was served a glass of the merlot. I tried the Kingston later. The meal came with bread and cheese and tea; it was nice to see eating approached with attention to health and enjoyment in contrast to the greasy fast-feeding American way. The airline was proudly pushing the Lord of the Rings film. They'd even painted a few of their 747s with gigantic murals depicting scenery from New Zealand and it was enough to make me want to travel there! I slept some, taking advantage of my pair of seats by the window to stretch out a little.

It was easy: go to the airport after work and arrive in a distant, foreign place before morning. Tahiti looked like paradise. I stepped down to teh tarmac, wet concrete, and smelled the warm sea air. Pretty young women handed each passenger a fragrant flower as we entered the terminal to have our passports stamped. At the greeting area hotel representatives met their guests with lovely flower leis and small cars whisked people away. The streets were quiet and peaceful; it was three o'clock in the morning. I wandered around the airport and the streets nearby, waiting for sunrise. Roosters crowed in the darkness and puddles shimmered in the orange light of the street lamps. Towards 5:00 I got in line to exchange currency, poorly choosing a time just after the arrival of a flight from Tokyo. When I got through the long line and stepped outside it was dawn and there, clear before me, was Tahiti. Pink clouds to the west silhouetted the craggy peaks of Moorea. Above the airport crumpled green valleys dotted with houses rose slowly to misty hilltops. I was excited; here I was in a beautiful place like none I had seen before.

I located a bus stop across the parking lot and joined a small group of airport arrivals there to wait for "le truck." The rough contraption eventually clattered to a halt nearby and we got on. It was indeed a truck, with seating for 16 on benches in the covered bed. A ride to anywhere on its loop cost 130F. The ride into Papeete was short and I happily stepped out and walked away with my lone bag as the other tourists wrestled their backpacks through the narrow doorway. It was 5:30 am and most shops were still closed. I quickly found the city markets and bought a tasty ham and egg sandwich on a baguette. Tables in the markets displayed produce, flowers, and souvenirs for sale. Tomatoes were the equivalent of $2 US each, cabbages $5, and small piles of a half dozen bananas or mangoes or papayas sold for about $3. Imported produce was obvious for its cost, and much of the food was imported. The market was in an open building with a corrugated steel roof and two levels, the upper of which sold only pearls, shells, carvings, and other tourism merchandise. Out on the curbside pareos of all colors hung on racks and lay on tables. Most women wore western style clothes but many of those were made of colorful floral prints just like the pareos. Deciding to return when more tables were uncovered and open for business, I set out to find the ferry terminal. A large ship, the Paul Gauguin, was anchored at the landing and next to it I found the ferry terminal. The sun had risen and it felt like midmorning especially with the time change, but it was still before 7am. I decided to wait for a later ferry and sat by the water to take in the city. Cleaning workers were collecting trash and sweeping and washing the flagstone plaza. Papeete was modern above what one would find in a developing country but still had the feel of being rougher than most American towns.

I took an 8:30 ferry to Moorea and stood on the top deck in the bright sun. I couldn't tell how many of the passengers were tourists and how many were residents; many Polynesians were vacationing for the holidays. Most people were speaking French and I could not understand a single word. I began to regret not having made time to study the language before traveling. I could find my way around but I would likely miss many opportunities to meet people. Hazy Moorea grew more distinct as we came closer. The water was a brilliant clear blue and the swells were small. Small flying fish shot out of the water and skimmed the surface for several yards before diving back in. I watched a gull scoop up and swallow one fish and wondered why the fish would put themselves at such risk. Maybe they were fleeing a bigger fish below, or showing off for the ladyfish. Showing off for the ladies is usually a foolish idea that gets one into trouble. The ferry passed through a break in the reef and docked at a landing beside two other ferries, both catamarans. The largest had many cars and even a fuel tanker inside. People were renting cars, renting motorcycles, returning their vehicles, and milling around; taxi drivers looked for passengers, vendors sold food, and people snapped photos of the lovely green crags that towered above us into blue sky. There were no other solo visitors. I looked around at all the happy groups of people setting off to their reserved hotels and wondered what to do next. The shore had looked peaceful and enticing on the way into the bay so I started walking along the narrow road toward the mouth of the bay. A couple hundred yards later I was ambling along the sandy beach watching land crabs scurry to their holes, coral crunching underfoot, sunlight filtering through palm fronds and waves lapping at my feet. The rush of traffic had passed and it was calm and quiet. The moment was beautiful but I needed to find a place to stay. If only I had brought a little green tent, surely I could have tucked it away in the forest unseen for a week.

I had a small map of the island but it didn't show the locations of hotels or banks or shops or the ferry landing. I knew which direction I was going but not where I had started from and as I walked I began to realize that it would take me a long time to get anyplace meaningful. I was considering where I might go when a car stopped behind me. A Polynesian woman dressed in a colorful pareo was smiling and saying something in French so I got in and we sped off. She spoke no English and no Spanish and I spoke no French. I thought hard about a destination to give her and remembered a village ahead called Papetoai. She replied with something in French and I didn't know if that meant she'd take me there or was stopping sooner. We passed the airport, beautiful turquoise shoals and white sandy beaches, clusters of shops and buildings and private homes. Several places looked inviting and I wished I could stop. Finally, having seen enough beautiful country blur past I spotted a sign for Pao Pao and conveyed my desire to be let off. The woman was confused and so was I. She dropped me at a grocery store and went in to buy something; I wondered if she had been planning to go there all along. I pretended to have plans and shuffled ahead, my flip flops thumping on the hot pavement. Around the next corner I saw the Club Bali Hai, a hotel I recall was listed as a mid-price place rather than high-price. That sounded good to me at least for the first night so I walked in and looked around. Located on Cook's Bay, the view from the open reception area swept from high craggy peaks to waves crashing on the reef at the mouth of the bay. Bungalows, flats, and timeshare condos were scattered about the site and there was a pool with an artificial waterfall beside a sandy beach and waterside restaurant. I was offered a room for approximately what I'd pay back home in Pasadena but it carried the shady request that I not tell anyone about my "special rate." Over the week I found that no other guests had wandered in directly so none could distinguish their cost from the trip package, but from brochures and inference I figured I was paying less than most but not as little as some lucky bargain hunters. Liking the thought of being done for the day, I stayed.

I paddled an outrigger canoe from the hotel out to the reef. I was told it would cost 500F per hour and dutifully paid, discovering later that some people hadn't been asked to pay. That, with the hush about my room rate, left me displeased with the service and put a dent in my impression of Polynesia. In South America, in Mexico, in East Africa I expected to be exploited and manipulated and given false information at every moment but I had for some reason expected Tahiti and Moorea to have higher standards of service. I felt that the price I was paying should have bought me a fair amount of trust. It was mud in the clear waters but the location was excellent, the people were fun, the snorkeling was beautiful, and I found nowhere else to go.

The common outrigger canoes were light open-deck fiberglass craft, most about 14 feet long and asymmetric, with a defined bow and stern and a 4-inch thick log for a float. The forward outrigger strut was heavier than the aft one and while the forward one was braced to immobilize the float in all directions, the aft outrigger was only a slender branch set to maintain the spacing between the float and the hull. The float had little reserve buoyancy with only one person in the canoe so it was, I heard, very tippy with two people. The craft really didn't handle very well - there was hardly enough room to paddle on the float side between the outriggers and when paddling with the wind on the float-side bow or stern there was a strong tendency for the boat to turn. In calm water I could keep it tracking straight paddling only on one side but usually I had to choose a side depending on the wind and spend much energy fighting to hold a course. Racing outriggers, in contrast, are sleek like a racing shell and are paddled with alternating short strokes, three or five on a side. Clearly it was valuable to have a well-designed canoe. In spite of the mechanical difficulties of my canoe I enjoyed very much being free on the water, paddling over the shoals by the reef with surf crashing, rugged mountains all around, and sunshine overhead. I could have circumnavigated the island had it not been for the sun. In an hour I was well cooked and for the rest of the week I had to remain in the shade, wondering how one could possibly enjoy the beautiful tropics without being burned.

As it was I didn't find much to do but read books from the communal hotel bookshelf, and snorkel, bicycle, and paddle. I rode to Belvedere overlook, a high point facing north towards the two bays, and descended through pastures and farmland to Opunohu Bay and rounded the northwest corner of the island. I bought a mango from a boy on the roadside and devoured the perfectly ripe fruit on the beach across the road, tearing off the skin and sinking my teeth into the sweet fruit without a care about the juice running down my hands. I splashed my face in the sea and looked out to the surf crashing on the reef, absolutely content and happy. Happy but thirsty, I rode on to a store and bought a drink. Life was simple. By midday I had returned the bicycle and was looking for something to do so I split a car with friends and drove around the island. It took the afternoon to snorkel and explore all the way around. The southern two-thirds of Moorea are residential, not particularly picturesque, and nearly devoid of tourists or tourist services including gas stations. The girl at the rental counter said the gas tank was empty but they wouldn't fill it; we would only need 700F of gas to drive anywhere we wanted to go. That bought us 5 liters of fuel and I was certain we would not have made it the 10 miles back to the rental agency when we finally found a gas station. The attendant didn't even bat an eye when I bought only 2 liters of fuel! Most vehicles were little Peugeot hatchbacks, some sputtering wrecks and others polished and sporting shiny rims, booming stereos, and tinted windows. Some people drove pickups, many rode motorcycles, and there were a fair number of bicycles. I couldn't imagine needing anything but a bicycle on an island that one could ride around in 5 hours or less, though it does rain a lot.

Food was costly in the way it would be in a North American city. Restaurant entrees ranged from $15-50 and breakfast or lunch could be had for $10 or $15. It was affordable but I never have been able to allow myself much expenditure when traveling alone. I don't need much for myself. Between restaurant meals I lived on bread and peanut butter and fruit and bottled water from the market up the street. There also I bought Tahitian beers for the evening happy hour with Muk and the guests. We gathered every evening at a table by the pool to listen to Muk tell yarns about the South Pacific, to learn about the good places to eat dinner, and to meet the other guests. The name Muk is derived from McCallum and probably had its roots in his years in the Service. In the late 50s he and his friends in Newport Beach, CA worked and partied and dreamed of exotic places to go; they had finished school and needed something new to keep them occupied. In 1959 Kelley was invited to sail on a yacht to the South Pacific and when he returned he told Muk and Jay, "Polynesia is the place for us." Finding a parcel of land on the island of Moorea for sale by an elderly California couple who had meant to relocate there but never did, the boys flew down to check it out and closed the sale. Kelley and Jay moved to Moorea in 1960 and Muk followed in 1961. They sold off everything they could to pay for the purchase and, with the plan of becoming rich vanilla farmers, they settled into the Polynesian way of life.

Muk could talk for hours and I would gladly listen to all he had to say. 74 years old, white-haired with a stiff walk, bluntly conservative and strong minded, he clearly knew how to be successful. The Chinese squatters on the property the three boys had bought had only kept about a hundred sticks of vanilla, he said, and shortly after they arrived the bottom dropped out of the market and they gave up the idea. The delicate orchids have to be hand-pollinated and unless prices are high it is difficult to profit from vanilla. In the early '60s tourism had not yet found Tahiti but the Islands were growing in popularity. Muk, Kelley, and Jay gathered together funds to build a hotel, the second then being constructed on the island. Unsuspecting friends from home were solicited for financial support and the design and planning was done by the intrepid trio. They called it the Club Bali Hai and soon Muk, Kelley, and Jay were known as the "Bali Hai Boys." A series of articles in Life and other publications romanticized the adventures of these three Californians. Muk appeared in a 1969 Super Bowl commercial shot on site. The numbers of visitors increased and the boys kept apace with them. Offering a lucrative dinner-and-lodging deal, they lured in flight attendants from international airlines; from then on their bar was filled every night with lovely Swedish girls in bikinis spending their layover at the Bali Hai. The Germans clashed with the Americans, the French annoyed people, Australians drank, and the Polynesians partied away every night. The hotel had a restaurant that Muk claimed to be the best in French Polynesia, a likely possibility given that there were few such places and the Bali Hai Boys had put together an excellent enterprise. "There is no money in hotels," said Muk. "I've never made a penny in the business but I've loved every minute of it." The costs of life are astounding - more than ten thousand dollars for electricity monthly for about 30 rooms, for example (could he have meant that price in Franks?). But the boys weren't in it for profit; they were living for the fun of it. None married. Muk had two children by 1 woman, another had 5 by 3 and the third 10 by 5. It was a life of lovely Polynesian ladies, parties, sunshine, and the ever-changing drama played by travelers from all over the world.

Times changed and unlike some hotel operators the Bali Hai Boys changed with them. They sold the hotel and built another on the profits, finding a smaller place more within their capabilities. They later closed down the restaurant because people don't eat where they stay; they chose to have a great hotel rather than a great restaurant. The evening bar was discontinued because fun-loving Tahitians love to drink and then they cause innumerable problems, disturbing guests and driving drunk and sneaking in youngsters to the bar. The nuclear tests in the Pacific slowed the flow of tourists but brought military men instead. Small riots and political incidents made to look big on camera nearly stopped the business but they kept it alive. In time Muk and Jay and Kelley took up farming again and turned over management to Rose, a Polynesian woman, and other staff. Jay died some years ago and Muk bunks with Kelley. The farm produces avocados and plantains and a variety of other crops; Muk still putters around there but he has men working for him. Every morning at 7:30 he drives past the Bali Hai and around the bay to the farm, and every evening at 5:30 sharp he's out by the pool for Happy Hour.

The other guests brought their wine and beer and pulled up chairs so every evening there was quite a crowd until hunger sent us scattering to dinner. The Kropps arrived with wine every evening, having brought glasses and bottles from home. They were suitcase vacationers, timeshare folks with too much luggage, new outfits for every day, and few intentions beyond sitting by the pool and entertaining the grandkid twins. Four years old and full of energy, the twins bounded and splashed around as their young parents attempted to relax. Jennifer, the lovely single schoolteacher, was (I learned from her folks) engaged and "too prissy to go in the water," spoken with a knowing mother's wink. The Australians brought excellent Bundaberg rum and tales of the south. Mick was in the Australian military, on leave for the holidays. He said "I'm sorry, but the American military is awful. They can't do anything. They see what we do and say 'that's awesome, I wish we could do that.'" I'm sure there's some truth to it, but the full truth is that the American military just can't be beat by anyone. We have so much of everything that we inevitably win. Mick went out running every morning to stay in shape until he stepped on an urchin one night. Once the spines were out the foot was fine, if sore, but the encounter made talk of skinny dipping trail off. Janelle and her mother were visiting from the Bay area, in Moorea for the weekend and going next to Bora Bora. They were very kind - Janelle's mother bought me dinner, and ice cream; we split the car, snorkeled at Temae, and shared several meals. The Italians never did join us in the evenings, probably since they spoke little English. The middle-aged Florida schoolteacher who wandered out one afternoon in a rainbow-colored speedo and asked if there were any nude beaches on the island was, despite his oddities or perhaps because of them, a good partner in conversation. He had visited 8 years before and found the island little changed. Many people were returning visitors come down from the States and many of those were from California. I'd first thought I was traveling someplace distant and exotic, but by week's end I realized that wasn't quite the case. Wendy and Charlie were from Pasadena. They lived a few miles away from me and had traveled in East Africa also, trekked to the Everest Base Camp, and snorkeled with me one afternoon off the closed-down hotel next to the Kaveka. Van, in from Virginia with Pam for a week on a package deal that cost little more than my airfare, had traveled in Peru and spent time in Puerto Maldonado and even gone to the same Wasai lodge and macaw clay lick that I visited last summer. It's a small and connected world, even in the middle of the South Pacific.

I bought a phone card, $15 good for about 17 minutes to the USA. The connection was good and when I called family and friends to wish them merry Christmas and hello I'm still alive it was just like calling across town save the short delay from query to response. I sat by the pool and finished a lengthy novel, happy that there were books to read since I'd brought none of my own. Without shoes I couldn't climb the mountains and it was probably better that way since they were steep, sunny, and hot. I was already sore, my feet chafed from walking with sand in my sandals, my ankles scraped from accidentally kicking coral, my shoulders sunburned from paddling, and my head suffering from the inevitable airport cold. Paradise was beating me up and I hadn't even done much of physical merit.

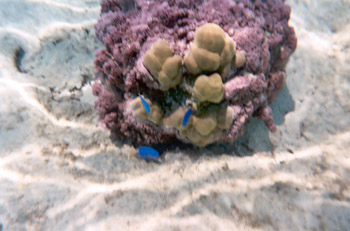

On Tuesday I decided to address the problem of idleness by throwing money at it. I booked the hotel's boat tour with shark and ray feeding and motu picnic. Much of the hotel went so it was a merry big crowd. We went out to a feeding site and watched as the daily fish were distributed to sharks 3-5 feet long that were entirely disinterested in a kicking mass of colorful swimsuits and skin. There was a heavy current towards the feeding and though we had a rope strung through the water to hang onto I, being restless, fought the current and snorkeled in circles and chased after sharks which, I found, were much better swimmers than I. Next we went to a ray feeding. There was little current and the graceful, slow creatures came gliding in and bumped among us in the chest-deep water to be hand-fed fish. Some sharks hovered in the deeper water nearby hoping for handouts as well, 'welfare fish' just like the Adirondack squirrels and chickadees are 'welfare animals.' We played with the rays for a while, I chasing after them, banking and turning above them, reaching out to touch their firm leathery skin. The boat went next to a motu where the staff grilled fish and served a lunch. I spent most of the time snorkeling near the reef; the coral there was the best I saw and there were many fish. Somehow I managed to get a fingertip in half of the photos I took with the underwater camera I'd brought! Too soon it was time to go back to the hotel, but there again I pulled up a chair for happy hour with Muk.

He painted a pleasant picture of life in the Islands. What could a Tahitian want? Medicine and care was socialized. Most people own their land. The minimum wage was about $1200 a month and families were fairly large so there was money to spend. $500 a month goes to the Chinese store. "That's a redundancy, Muk said. The Chinese run all the stores. $500 a month goes to the Chinaman... " I stand down and speak fairly myself to keep the peace but I will take sides with the man who says it as it is and finds humor, though not inferiority, in differences of race and culture. $500 a month goes to the payment on the extended cab pickup. The rest is for spending. I suspect that the situation is a little more complicated than that but it appeared that most people had sufficient living wages. Crime is quite low in French Polynesia. Education is well-funded and is taught only by instructors schooled in France. The best students can study in Paris, funded by the government. But there just wasn't much to do in Polynesia besides small farming, small fishing, and tourism. Tahitians are by nature not hard workers because there is little reason to work hard. They can't freeze, they can't go hungry because food grows on the trees and swims in the sea, and the island is so isolated that there isn't an unlimited volume of things to do and buy, there isn't an endless ladder to climb, and there aren't many reasons to be unhappy.

For me, however, being a visitor and having a particular drive to accomplish things and seek challenges and climb higher, the islands seemed sleepy and unrewarding. They were certainly beautiful. The mountains are untouched and nearly unreachable, the water is clear and pure, the trees very green and lush, the flowers always blooming and fragrant. Beautiful women abound and at some beaches many are topless. The people dress colorfully and are friendly but shy. The food is French and delicious. Travelers usually spoke my language and invited me into their circles. The trouble was that there was nothing beyond these pleasantries. The island was a plateau of existence, a stable place of little drama and little concern. Even the natural wonders had lost their allure by week's end. The place was finite and I could walk around it and see all there was to see in a matter of time. I was well aware of the huge unexplored ocean wilderness that surrounded me but it had required no effort to cross it by air. The call of the sea has somehow been trounced by aircraft and it seemed that humankind no longer can have the satisfaction of arriving in an exotic and distant place after braving the great oceans. One would have to ignore the alternate routes to do so, though there are very many places only accessible by boat.

Tahiti is a popular honeymoon destination especially in the summer months (November through February would typically be a rainy, windy season if the region was not suffering from a 6 year long drought.) Had I arrived with a lady and hopes of a dreamy vacation, however, I think I would have seen the experience fall short of the dreams. Buildings have a hint of blocky 1950s architecture that I find very depressing. Aluminum windows and doors, plain clapboards, chain link fences, and boxy designs with little aesthetic appeal make me think of the company town with the housewife wearing an apron, the smiling children meeting the father returning home from the office, and life lived by television. That's a big part of Middle America but I shudder from the thought of it. I'd rather live in a beautiful shack of corrugated steel and rough planks with the character and pride of the builder in every hammer mark. I've heard that the other islands are different and that farther away from Tahiti one will find a different slice of paradise. Maybe some day I'll be by to see for myself.

Friday I decided I must move. I packed my bag, checked out of the Bali Hai, and began walking towards the ferry landing. As I reached the road I saw Muk driving past in the other direction on his way to the farm, at 7:30 just like every morning. He honked and waved and I waved in return. Farewell, friend, I am but a passing visitor to your island but I am taking with me many thoughts. The sun was not yet strong and I was confident that I would get a ride before long. It was only a matter of waiting; probability stated that I would get to Vaiare eventually. The situation called for patience: I need not struggle and agonize about such a certain eventuality but it was frustrating to wait. I had little time to think this through because a boat boy from the Bali Hai picked me up and took me a couple miles ahead. Next a pickup stopped for me and I hopped in back under the canvas top. A cardboard crate that had held Tahitian beers slid around in the bed. It felt good to be speeding along in the back of a truck alone in a foreign country again. I was wearing a white button-down shirt with the sleeves rolled up to the elbows and slacks and flip-flops and sunglasses. I felt free and strong, a step ahead of the backpackers and yards ahead of the suitcase-toting vacationers. Well dressed, wild, and willing to go wherever my truck was headed, I smiled to myself as the police at a checkpoint spun around to see me as we sped past. There is nothing unusual about a person in the bed of a pickup in Moorea but I was no Tahitian. I was different, perhaps a bit dangerous.

The ride and my daydreams ended at the ferry terminal. I thanked the driver and walked to the ticket booth to check the schedule. The next ferry was in two hours. I bought a bag of fruit and was disappointed to find that the crunchy mango slices weren't ripe but had been colored from greenish-yellow to ripe red-orange by a powdered drink mix. I tossed the bag in a trash can and sat watching the water. A 500F note skittered across the pavement in the breeze just inches from the edge of the landing, about to fall in the water. I shuffled over and captured it, seeing no one chasing it. I had been compensated for the false marketing of outrigger canoes; the gods were sympathetic! Looking up at the mountains I saw the Window, a hole clear through the sharp toothy summit of 2490 meter high Mouaputa. It looked so near that I decided I could make it up and down before the evening ferry. I had water and time; why not go exploring? I walked off down the road to look for a way into the hills. It was hot, and my right foot was still sore from sand and coral. I could find no way to the ridge that didn't go through a private drive or a yard and I began to see how difficult the climb would be. I might thrash through jungle for half a day and end up at an impassable cliff. Defeated, I returned to the ferry terminal and waited for the ferry.

This time on the ferry I sat inside the cushy cabin on an upholstered seat by the tinted windows. Music was playing and I suddenly was very sleepy. I hadn't done much but sleep and read in previous days and had no reason to be tired but there wasn't much to be excited about either. In Papeete I found a room and then went out to see the city. Many shops were closed for the Christmas weekend. I walked through the park on Boulevard Pomare and looked through the markets and the pearl stores. Every store had black pearls for sale. There were rough pearls for a couple dollars each and fine dark spheres for several hundred dollars apiece. Shell carvings, wooden figures, woven panadus hats and handbags, necklaces, trinkets, and colorful pareos filled the shelves. I spent half my remaining money, walked up and down the waterfront, and watched time pass. Money could rent me a car or buy an afternoon at a bar but neither held much return for me. Waiting is part of traveling; one sees the sights and more often than not there is time left over. I waited for sunset and found a place on the water to watch brilliant colors seep into the sky behind the jagged peaks of Moorea. We never did get much of a sunset in Cook's Bay and I was happy to have seen this one.

I sat down for dinner at a restaurant where a band was playing but soon they packed up and left. It was not yet 7pm! The streets were not very busy and the nightclubs were not obvious. Papeete was regarded by many people I spoke with as a polluted, crowded, drug-ridden metropolis. I found it presentable and well kept, though busy with traffic. I felt relatively safe on the streets; only a handful of beggars asked for handouts and the sleeping drunks kept off the main thoroughfare. I could not be distinguished from a resident and there was nothing about my appearance to signify wealth. Indeed, I was for once in my travels not vastly wealthy in comparison with the population. It felt good to be able to travel among the people instead of above them. There was no reason to be out on the streets after dark though so I returned to my hotel and slept for 10 hours.

Saturday was a repeat of Friday: waiting, spending money but buying little worth remembering. At last I was at the airport and it was late and we were about to depart. Twelve Bali Hai guests were departing with me. Barry had been out surfing on Tahiti with some Australians he'd met and had his board stolen from the roof of their car. Someone cut the straps in broad daylight and got two nice boards and board bags and accessories. It's a shame but foolish too; I may be paranoid but I have yet to find a place where I trust people. We shopped the duty-free stores and I packed some liqueur for New Year's into my small but seemingly bottomless bag. The hour of departure arrived. I climbed into the plane, stretched out on my three seats, and went to sleep.

The story ends but of course I go on with another. Los Angeles is just as fascinating as French Polynesia but I've become accustomed to it. Leave the familiar and you'll learn about both the place you've traveled to and the place you've left. The plane roared on for hours and suddenly there was a continent, a coastline stretching off in both directions for thousands of miles and a chilly brown city of millions perched there at the edge of the blue void we had crossed. The freeways were packed with people on the move. Snow shimmered on mountaintops eighty miles to the east. Brown leaves blew across hard pavement and palm fronds shook in a stiff breeze. In the lush landscape of French Polynesia lives were drifting along slowly as they had for hundreds of years but here on the hard and tangible continent there was a battle to fight, success to be had, progress to make, and a dream to pursue.