Sixteen Days South with Joy.

Sixteen days on the South Island were enough to circle much of the perimeter from Christchurch through Kaikoura to Nelson, Greymouth, Haast, Dunedin, and Oamaru. Along the way we ate wonderful seafood, sampled wine from the vineyards of Marlborough, hiked along golden sandy beaches, drove desolate roads along wind-whipped coastline backed by soaring snowy mountains, crossed sheep-filled pastures, and explored quiet little towns.

Something had gone wrong with my flight to visit Joy. It took far too long, for one thing, and the plane was huge and the attendants gave me food and wine and I had three seats to strech out on. It was annoying that the arm rests wouldn't fold back all the way - I couldn't lie flat. This led to fitful sleep, leaving me tired and bewildered when I gathered my things, put on my shoes, and walked off the plane into the terminal. Joy was there but a thick pane of glass separated us and there was no way around it and we could only hear each other through an air vent. As I walked outside and glanced around at some strangely symmetric pine trees I wondered if this was how Alice felt in wonderland.

I got on another airplane and flew to another airport and then Joy appeared again, this time without the glass wall. We took a shuttle van across the city and rented a car, but the car was all put together wrong with the steering wheel on the wrong side and the turn signal reversed. To open the driver's side door I had to turn the key as if to lock it, and the roads were backwards and painted differently too. Otherwise everything seemed more or less unchanged from the way California had been six months earlier: rain showers marched across fields lush with green grass and wildflowers and orange California poppies swayed in the breeze at the roadside and little balls of wool grazed on hillsides in great herds, oblivious to the weather. There aren't really sheep in California, but it seemed that everything was a little strange so it wasn't all that surprising to me that there were sheep.

Hungry after the long restless night, we drove up a gravel road to a winery restaurant and ordered up a lavish meal. The steak was tender like warm bread and drenched in a savory sauce with little morel mushrooms cast about in a flood of flavors, and the walnut zucchini soup was mouth watering and rich - and complimentary, hence its presentation in a woefully small teacup. We finished with a small custard inverted on an immense plate and garnished with white figs and a splash of strawberry. "Vacation!" we said as we left a substantial part of our colorful foreign cash on the table and turned our car northward on the small country road, taking care to keep to the left side. The bewilderment was being replaced by a feeling of peaceful satisfaction - we were basking in the pleasure of spending two and a half weeks together in springtime bliss far from home with lovely seacoast on our right, towering snowy mountains on our left, and unknown wonders ahead up the road. That's why we came to New Zealand.

Our long journey came to a close in the fishing village of Kaikoura, a windy spear of green grass and chalky cliffs jutting out into the Pacific Ocean two hours north of Christchurch. It seemed like a sleepy town despite all the shops and restaurants packed along its two hundred meters of downtown strip, probably on account of the gray weather and late hour. We started to walk up a clifftop track but ornery cows suggested that we turn back so instead we went along the water's edge and saw many shells in the clean, clear, cold blue water, got soaked by a steady rain, and turned back to seek shelter like the two wet sheep we passed along the way. We bought fish and chips for dinner and took the paper-wrapped parcels back to our room at a hostel called The Lazy Shag where we devoured grease-laden morsels and wished for dipping sauce.

The kitchen at the hostel had separate bins for plastics, paper, and pig food. It turns out that the food scraps actually do go to a pig. We sipped hot tea and looked with restrained hope out the windows at tree branches whipping about in gusts of wind, willing the weather to clear so we could go out on a boat to look for whales. Kaikoura has built a lucrative business around showing the local marine animals - whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, and the like - to visitors and on selling crayfish aka lobsters to those same visitors. We resolved to wait until midday to see if any boats would venture out into the choppy sea and drove to the top of the peninsula to pass the time. The wind there was chilly and strong enough to make standing difficult so for a while we sat in the car and watched ripples propagate across an ocean of tall grass. The clouds were breaking up over mountains to the west and we caught glimpses of their tall craggy summits bathed in sunlight. On the south side of the peninsula, brilliant blue waves crashed ashore on a stunning black pebble beach. I wanted to scoop up the pebbles and fill my duffel bag with them, but it seemed such a silly thing to do when the entire beach was covered with them.

I suggested we drive inland to seek those sunny slopes in the hills. By the time we approached them clouds had returned and the landscape was asleep again under its cool gray blanket of mist so I turned the car back and got a bowl of hot seafood chowder in town. It came with wonderful crisp triangles of buttered toast. The weather looked uncooperative so when the soup was gone and only crumbs of toast remained we walked back to the whale watch headquarters to hear the verdict: all sailings would be canceled. We joined the weary stream of people returning to their cars and drove directly to Pipi's Restaurant north of town for a consolation meal of lobster and steamed green mussels.

The meal proved to be just the thing to set the day's events back on course. A large steel pot of big juicy mussels steeped in herbs and garlic was promptly delivered followed by a half lobster broiled to perfection. New Zealand knows it's way around seafood in the kitchen! Once the last fragment of shell was moved from pot to bowl and sticky fingers were all rinsed clean, we paid our bill and set off northward again. There were seals, gulls, spiral blue shells, gray pebble beaches, and stunning rugged hills draped with the densest foliage I'd ever seen. The clouds thinned out, the ocean turned from blue gray to deep cyan, and I discovered at one point that we were standing in an extensive forest of giant wild fennel plants. These were beside a lovely gray gravel beach with dark sand dunes and stiff green tufts of grass that traced out concentric circles in the sand as they blew around in the wind. The beaches were all trackless and the only inhabitants of adjacent hillsides grazed peacefully. I wondered if the sheep truly appreciated the scenery spread out before them.

That evening, I endeavored to find out if happy sheep - presumably the sheep grazing beachside in lush fields were as content as sheep can be - might taste better on account of their gentle lifestyle. The comparison was to be made against the unfortunate sheep of Xinjiang, China, which had to search for bits of grass in either searing hot weather of the Taklimakan Desert or frigid dusty winds blasting down off Central Asia's towering mountain ranges. Joy and I were dining at Hunter's Vineyard in Blenheim, in the heart of the South Island's Marlborough wine region, and I had before me a shank of lamb stood unnaturally at the center of a plate. I wonder why they do that - why chefs balance a tippy piece of mutton led on end like an upside-down icicle, position potatoes and onions around it, lay a sprig of watercress on top, and call it lamb even though its size clearly indicates that the creature had long ago exited the phase of cute frolicking baby animal and become a slow moving ruminant lacking both tenderness and cuteness. I tapped my balanced lamb shank lightly with a fork and it toppled over to a more edible position. The meat, I found, was no less tough even with all the green grass and blue water.

The sheep eating was, however, later in the evening after we had raced with the sun against advancing clouds into Blenheim to the Antares bed-and-breakfast. Our nicest (and most expensive) accommodation of the trip, the homestay was situated among olive groves, lemon trees, and vineyards with a comfortable lounge area stocked with movies and books, a steaming hot tub outside, fluffy terrycloth bathrobes, lemon-scented soaps, two dogs, a friendly gray mohair goat, and a cat. There was an electric blanket too, but I found that somewhat scary and didn't gather the courage to turn it on. It was Friday night so most of the vineyard restaurants were booked but Heidi at Gibbs phoned Hunters restaurant and held a table for us. It's nice to see business neighbors be so generous.

The cat at Hunters had learned the menu well. Anticipating a forthcoming meal, it scampered in the door as the sun sank low, surveyed the guests, and after venturing around the room several times identified our table as one of those most probable to dispense food. Worn down by the cat's steady gaze, I was about to surrender my fragments of mutton fat when a waiter cleared the plates away. I should have been stronger, though; our companions at the next table then discovered that the clever animal was snobbishly turning its tail to grilled salmon and demanding roast venison instead. I felt a little embarrassed at having been duped by a cat, and on top of that the car was still all backwards after dinner. We drove back to our room and went straight to the hot tub.

Birds woke me in the morning. There was a nest somewhere in the space above our ceiling and the baby birds were very hungry and all the other birds outside were singing too. It was pretty, and the sun was shining, and we were excited about bicycling from winery to winery so rising early didn't seem unpleasant. Our host Jane cooked a wonderful meal of eggs and bacon and warm croissants and toast and jam and fresh squeezed orange juice and we chatted with Arnie and his wife (fellow travelers from Canada) before putting our bags in the car and setting out with maps and bicycles specially fitted with wine bottle carriers. We rode around and tasted wine and bought some bottles and talked to a stone sculptor who went to school a few miles from my apartment back home. He cautioned us about the sun - there's very little ozone down there, and it doesn't take long for skin to burn. I'd heard that before but hearing it again from someone who came from the States and works mostly outside made it sink in deeper. I knew there had to be something wrong with New Zealand - nothing can be perfect.

We ate ginger pumpkin soup and a delicious walnut pesto cheese quiche at Highlands, a winery atop a small rise, and then finished the meal with a square of tiramisu. Little birds flitted around in wire sculptures at the edge of the patio where we sat looking out across the vineyards while a gusty breeze tried to steak our napkins. The ride back seemed longer than our excited explorations earlier in the day so I was glad that our next accommodation was just a fifteen minute drive away, even considering our brief stop to buy a box of fresh cherries.

The Beaver Bed and Breakfast, I learned, took its name from the consensus of the first European settlers that the area was so wet from frequent river floodings that no animals but beavers could live there. It would be unfair - after all, the landscape looks so familiar - to point out that no beavers lived in New Zealand, nor any other furry animals aside from several small species of bat and the rats brought by Polynesian settlers in their canoes (wouldn't you think that one would easily notice and dispatch of any stowaway rats within a few days of embarking across open ocean in a canoe?). A system of levees now keeps the river in check and out fo the vineyards, for the most part, and introduced furry animals run rampant.

We went to a pizzeria for dinner and ate a tasty pizza. I had an excellent dark Scottish ale that had its origins several meters away in a large steel tank in a dim room behind glass. Music played, dishes clinked, and I decided I could get used to a life of meandering around the stunning countryside sampling good food and drink. However, our plans were somehwat different and so we spent the rest of the evening re-packing food and equipment for our walk through Abel Tasman National Park. There were meals to pack, fuel bottles to fill with the white gas I'd found on a shelf at a petrol station in Kaikoura, and clothes to cram into our suddenly heavy backpacks. Walking wasn't going to be easy no matter how much the beaches might look like paradise.

In the morning we set off driving north and took a detour to a high overlook above Marlborough Sound. The view of rugged islands made by sunken mountain ranges reaching out into the blue ocean was framed by tree ferns and lush forest with familiar clusters of white field daisies nonchalantly growing by the roadside as if there was nothing odd about their appearance so far from home in such a strange landscape. Marlborough is at the same latitude as Massachusetts, but then why didn't I get any cool Jurassic tree ferns to hunt dinosaurs in when I was a kid?

Farther on we came upon the city of Nelson. It was the most populous place I'd driven through since Christchurch and I found navigating through the web of streets to be very distressing. We parked and walked around a little, picked up some maps at the i-site information center (there's one in every town), and then retreated (or advanced, I should say) north out of town to The Boat Shed. A restaurant on stilts at the edge of the Abel Tasman bay, the Boat Shed was fitted with all sorts of fish-themed decor and sported a menu worthy of the location. Joy sweetly tore apart and ate a large snow crab and I munched my way through an exquisite seared yellowfin tuna steak bedded on shrimp-studded fresh herb linguini, topped with floppy bacon, thin slabs of parmesan, a few scattered stems of watercress, and a sweet chili vinaigrette. The thing was absolutely beautiful, and it cost only twenty dollars! New Zealand dollars, mind you. My compliments go to the restaurant and the chef.

From there on out the countryside became increasingly sparse and unexciting. We arrived in the village - just a few buildings, really - of Marahau late in the afternoon at low tide when the water was far away beyond shimmering mud flats and people were ambling back to their cars after a Sunday afternoon in the Park. Our Hostel, The Barn, was clean and neat but signs in our room asking that we "attend to our packs, sleeping bags, etc. outside to help with the bed bug problem" left us a little uneasy. We cooked a meal of rice and beans in the shared kitchen and tried to get to sleep early. Sometime during the night - which was free of bed bugs - I went outside and was thrilled to see that the sky had cleared and was showing off a spectacular splash of stars I'd never seen before. Big bright stars were scattered all over the sky and smaller ones filled in everywhere, not just in a narrow band like they do in the Northern Hemisphere. You've seen the fake-looking star-scapes in movies and theaters: it turns out those aren't fake after all, but rather Southern stars in their proper places.

By morning water had returned to cover the muddy shoreline and the grass was drenched in dew. A mile down the road from The Barn we clambered into a trailered aluminum boat with a hefty 225 horsepower outboard motor. Our bags were all loaded in the front and we sat on benches with sixteen other people wearing orange flotation vests. A farm tractor towed us out to the water (the gnarly tires and high ground clearance come in handy when the tide is out and the trailer must be towed through mud and puddles) and we pushed off, our barefoot captain dispensing local lore in a well-practiced routine as we moved up the coast. The boat stopped many times on its way north, dropping an anchor off the bow each time before backing in to the sandy beach so the boat could be winched back out to sea by drawing in the anchor chain.

Two hours later we hopped off the boat at Mutton Cove, splashing barefoot through the shallows and dropping our packs on the golden sand. We waved farewell and surveyed the scene as the hum of the outboard motor faded away: little waves lapped at the beach and a cool breeze rustled leaves but otherwise it was quiet. There were a few other people there though none had come from our boat. We put our shoes back on, adjusted our packs, and set out to the north for Separation Point, a rocky outcrop that looked like a perfect lunch stop. The wet sand was packed hard and made for easy walking. Pink flowers swayed among verdant grass. Soon the trail turned inland and climbed steeply, but the air was cool and walking was pleasant.

Separation Point looks out over the big blue sea between the North and South islands of New Zealand. A thin ribbon of land called Farewell Spit shields the Abel Tasman coast from westerly weather and to the east the islands and peninsulas of Marlborough Sound block swells from the Pacific Ocean. I scrambled down a steep path almost giddy with excitement: furry animals were swimming back and forth in the turquoise water right below the point! They were sea lions, often seen back home in California but never in such a stunning setting. Cormorants perched nearby at the edge of the rocks. They are graceful birds, but the terrible stench that wafted off the rocks from fishy bird poo overpowered any admiration I might have had for them. We took photos and then retired to a sunny ledge to eat lunch but our meal was interrupted a short time later when Joy noticed something approaching in the water. Dark churning bodies were rounding a bend in the coast and suddenly two dark fins cut past just a few meters from where we sat!

They were dolphins, an uncommon sight there along the coast. Perhaps a dozen animals swam around the point, porpoising and splashing and diving. The last one in the group slapped the water with its tail at every stroke and later, when the pod had stopped to explore and inlet beside the point, we heard their voices honking like geese and making clucking sounds all in one complicated and beautiful language. They were still there splashing in the shallows when we hiked back up the point and turned inland on the trail south.

The trail climbed high quickly, rising through dripping forest covered in ferns and bright green grass. Vines hung from trees and rivulets of water ran across the path. From time to time we saw views of the beach far below and after a while we descended to it. Our first campsite at Anapai Bay was just beyond the next headland but getting there took longer than I expected because the trail went up and over the top rather than across the steep face of the hill. Anapai has three hundred meters of golden sand and three or four clearings at the edge of the forest where tents could be put up. No one else was there so we selected the best spot, put up the tent under the shelter of overhanging trees, and walked out to explore the tide pools. The wind had picked up and the tide was out but the beach fell away more steeply than it had at Marahau and there were no mud flats even with the four meter tidal swing. A gull was trying to swallow a large flat fish, the kind that lives against the sand in shallow water. The poor gull knew that normally slender little fish go down easy, but it was discovering that there was no way this pancake of a fish was going to fit down its narrow neck. Experiences such as this led to evolution of teeth and opposable thumbs and to the invention of the knife.

At the south end of the beach, rocks harbored all sorts of creatures - green and black mussels, urchins, sea stars, tiny fish, and various slippery sea plants that squelched underfoot and made walking hazardous. We explored for a long time, hopping among the rocks until the tide started coming back in. I found a little abalone shell and Joy pulled a beautiful green urchin shell from a crevice underwater. I felt like a kid, romping around at the edge of the water collecting shells.

The water was too cold to swim. The mussels were too small to eat and we had no license to harvest them. Other than that, everything was absolutely perfect until dusk fell in the middle of dinner and tiny black flies emerged to chew holes in our skin. As biting insects go black flies in small quantities aren't all that bad - they're slow and easily swatted and they can't bite through clothes - but nonetheless they made eating difficult. We tried sitting out on the beach but the breeze had subsided so instead we retreated to the tent and set the warm pot of pasta on a towel. In New Zealand there aren't many animals that would chew or claw their way into a tent for food, and none of those are larger than a football, so I wasn't particularly worried about getting crumbs on the floor. After we were finished eating I hung the food from a tree, counterbalanced six feet high and well out of reach of even the most creative possums.

Sunset colors faded from the sky and waves lapped on shore. The tide was creeping back in and the lighthouse on Farewell Spit had come on, many miles away across the waves. We had the entire beach and all the campsites to ourselves. The outhouse even had a flush toilet! We made tea and went out for a walk on the beach where I created the grandest flood control dam the little sandy stream by our camp had ever seen. It held back a huge reservoir, flooding the plains upstream much to Joy's dismay. Then the dam broke - with a little help - and massive destruction was brought upon the stately sandcastles downstream. Silly of them to build in a floodplain - what were they thinking? Later in the evening a stunning starscape emerged, even more spectacular than it had been the night before. The flies were gone, subdued by the night chill that was also squeezing dewdrops from the air. We put on our warm clothes, spread towels on the beach, and lay there admiring the stars for a long time. I was convinced that a particular set of four stars was the Southern Cross, but later I realized it hadn't quite looked like the pictures we saw on postcards. Meteors streaked overhead and satellites cruised through the star fields. There was no moon, just starlight shimmering on the waves. Little green sparkles if light from tiny bioluminescent sea creatures flashed in the water when I ran my hand through it. The evening was perfect.

The tent was soaked in the morning and sand stuck to everything that was wet: flip-flops, foam mats, cooking pots. There was a dramatic bank of clouds offshore to the north that looked like it could be a weather system moving in. We waited for sun hoping it would dry things but when the clouds broke the warmth brought out the little back flies. I put on a fleece and thick socks and got to work on breakfast: pancakes soon sizzled in hot oil. We munched our way through crispy little cakes drenched in maple syrup, one at a time. After a while the sun got hot and the flies went away. We dried the tent, packed everything away, and meandered on up the trail mid-morning. It rose through the prettiest rainforest yet, climbing through a ravine of beech trees and thick jungle before dropping down to the urban-feeling beach at Totaranui. A road comes in there and we saw cars and vending machines and a grove of giant trees planted when the fields were farmed by early settlers.

We couldn't get much farther. By one o'clock we were standing at the edge of a vast blue inlet where the trail disappeared underwater. Crossing could only be made within two hours of low tide, and we knew this earliest crossing would still be two hours away. We ate lunch, and the water receded fifty meters. We chased little crabs into their holes - there were thousands of crabs, none bigger than a 25-cent coin - and the water receded another fifty meters. Two girls from Israel arrived and looked out impatiently at the crossing. They were in New Zealand for ten months, they said - they had lots of time and not so much money. I think I prefer a refreshing, well-supplied, short trip over a long and lean one. After a while they walked out across the mudand we watched them try one part of the channel, turn back, move one way or the other, and try again. A while later we set out ourselves, bare feet squishing through the mud. There were sharp-edged clam shells lying in drifts where the currents had cast them but flip-flops wouldn't stay on our feet in the sticky mud so we stepped carefully. The mud and gravel underfoot actually felt like a massage. By the time we got to it, the remaining water in the channel was only thigh-deep and swiftly rushing out to sea.

Two more hours of hiking took us to our next campsite at Tonga Beach. Along the way we passed the Awaroa Lodge, an eco-touris accommodation also accessible by road. Fresh food from a garden supplies the kitchen and well-to-do visitors can travel by small plane to the grass airstrip that runs along Awaroa Beach. At Tonga, slabs of gray granite from short-lived quarry operations dating back a hundred years or so lay scattered at the edge of the sand. The beaches of Abel Tasman are granite too, but iron from the sea has turned the sand orange. We put up the tent and organized our things to be ready when the black flies came out. After dinner I brewed a bottle of mint tea and we walked on the beach while the sun set, sipping tea and collecting more shells. A young couple from Spain arrived and camped beyond some boulders; we didn't see them except when the girl came to see if we had any extra plastic they could have. They'd forgotten to bring the rain fly for their tent but fortunately, it didn't rain that night.

In the morning we did the short walk to lovely Bark Bay and continued to Medlands Beach. This was our planned camping spot but we were there by noon and there wasn't really much to do in the area. I'd thought we might be able to go snorkeling or explore the adjacent hills but the water was cold and we'd been hiking through the hills for two days already. We made some soup for lunch and decided to move on to Te Pukatea Bay so we could get out of the park a day early and possibly see something else. New Zealand has so much to offer it didn't seem right to linger at Abel Tasman. Also our solitude had diminished: dozens of people passed on the trail and the beaches were visited frequently by boats. We crossed more mud flats at Torrent Bay, this time arriving at low tide and proceeding directly to the other side. At Te Pukatea, we found a spot for our tent in a small clearing in line with eleven other tents and were relieved when the ranger checking permits said our change of plans was ok.

Just after I finished cooking dinner a weather front arrived with powerful gusts of wind. Sand blasted through the thin trees shielding us from the sea and my tent looked as if it was about to collapse. We set our food aside and moved the tent to an adjacent site that had better shelter from a seaward wind, carrying it with everything inside. The wind calmed down after that but big waves crashed on shore for the rest of the evening. Sand had blown into the crevices of our packs, through the mesh and into the tent, and even into our covered pot of rice so the meal was a little gritty, but at least there were no flies. We went to sleep early and only woke once to the sound of raindrops falling softly on the tent.

The short rain only wet the beach sand a few centimeters deep. We got an early start but several groups had already packed up and left by the time we finished our breakfast and dried out the tent. The walk out seemed endless and choked with people. There were occasional overlooks of the bays and islands but for the most part the trail was high, dry, and widely cut; no where near as nice as the northern section had been. A better plan would have been to take a bus to the far northern end of the trail, stay at Anapai and Tonga, and then take a water taxi back from Awaroa to see the rest of the coastline. I jogged back to the lot where our car was parked. By the time I got there five minutes later my feet were hurting, sore from trying to pull stuck sandals from sticky mud step after step. Joy had some blisters and the bug bites were bothering her more than me. We were broken!

It was midday but we weren't very hungry. At a store in Motueka I bought some groceries and got tangled up in traffic that understood New Zealand rules-of-the-road better than I did: It's expected that when two cars driving towards each other on their respective sides of the road both find themselves waiting to turn onto a driveway or side street, the car not crossing a lane will yield to the other car. It works marvelously and I think we should adopt this practice in the States, if only everyone could be taught it at once. There's little room for misunderstanding.

The road we followed south angled through a rural valley flanked by lovely green hills dotted with grazing sheep. The scenery really was superb: trees sported the season's finest shades of green and wildflowers were blooming everywhere. At one field I saw hops for the first time, strange looking vines growing up wires hung in neat rows. A short way down the road I spotted a forlorn young lamb pacing back and forth at the edge of the road, looking in on a pen full of lambs. It must have squeezed out under the fence - there were lots of places a small sheep could get through. The road was heavily traveled and cars blasted past at great speed so I was careful not to scare the frightened animal into the road as I cornered it and carried it back to its pen. It went limp like a big wooly doll with green eyes and little hooves until I set it down in the close-cropped grass, at which point it sprang back to life and vanished into the herd.

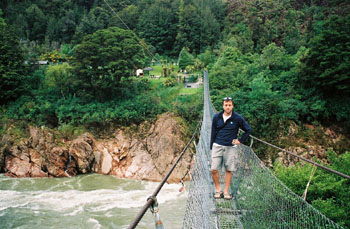

The excitement of rescuing a baby sheep gradually wore off as I drove out of the sun-drenched green hills of the Motueka valley and into the damp gray Buller River watershed. We stopped at a suspension footbridge over the rain-swollen river and walked across sixty feet above the roiling brown water, stepping lightly and taking great care not to drop the car keys or any other indispensible item. On the other side of the bridge we realized that we'd been sold on a sad tourist trap, a feeble attempt to delay passing travelers by presenting rusting machinery along poorly-maintained trails overrun by out-of-control weeds and grass. On top of that signs warned us at entrance and exit that the terrible diddymo algae had invaded the area and that we should wash everything that had touched water with bleach to make sure the disgusting sludge didn't migrate onward to pristine waterways. Since it was raining and everything was wet, we figured that our shoes had been contaminated. Later that evening they went into hot water and every surviving strand of evil algae was cooked till its death was certain.

The Buller River Gorge led us to the town of Westport late in the afternoon. Intermittent rain and gray clouds hung heavily overhead. I'd picked up a brochure for the Westport Motor Inn when we were in Nelson and as it happened, the place was the first one we came to on a deserted side street. A room was available for 85 dollars, it had a hot plate and kitchen sink and dishes and small refrigerator, there were coin operated washers and dryers, and a tiny one-third liter bottle of milk was given to us with the room key. What more could we want? Clothes went into the washers, the milk went into a pan with our remaining camp meal of macaroni and powdered cheese, and fresh fruit I'd bought earlier finished off the meal. We strung a cord across the room to dry the things that were still damp after the dryer stopped and then went to sleep, happy to be clean once again.

I mixed up the rest of our pancake batter in the morning, finding cooking much easier with a nonstick pan and a big hotplate instead of my little steel pan and camp stove. There was a little maple syrup left too, which we finished. We gathered all the clothes and equipment together and headed into town around 10am. It seemed more alive than it had the night before but the sky was still gray and a stiff wind whipped up big waves off the aptly-named Cape Foulwind south of town where we watched huge quarry trucks big enough to carry ten of our cars lumber across the road, making the trip between quarry and processing plant. There didn't seem to be much besides the quarry operations and visitor services to offer employment and it made me wonder how people made their livings so far from almost everything.

Highway 6 wound along the wet and rugged west coast, arcing past steep cliffs and meandering through forests until it suddenly delivered us at a bustling clearing in the shrubbery where paths cut through dense foliage led out to a breathtaking scene of layered limestone formations, sea stacks, arches, and holes that rumbled, gurgled, and belched white mist as waves surged into chambers far below. Pancake Rocks, as they're called, are a major tourist stop and one of the only really neat things to see between Abel Tasman and the glaciers farther south. Fortunately, the drive is easily done in a day. By noontime we were in Greymouth and rain was once again falling from the gray sky. Nearly every shop and restaurant on the main street had a roof or awning extending over the sidewalk to shield customers from the incessant rain as much as possible.

We'd been seeing signs for whitebait, a kind of immature fish a couple inches long and thinner than a shoelace that is cooked into all sorts of delicacies. People catch the fish with nest at a particular time of year and some sell them from their homes, advertising with hand painted signs posted streetside. The tasty creatures fetch seventy dollars a kilogram, the equivalent of 20 dollars a pound. The restaurant we tried served them in an omelette where butter and eggs mostly overpowered the flavor but we got the idea: delicate, boneless little slivers of fish with a texture sort of like linguini pasta and a fine seafood flavor. The restaurant was cozy, with a fireplace and warm colors and rain pattering overhead on the skylight so we lingered a while before driving on down the narrow two-lane road that at times shared one-lane bridges with operating railroad tracks. The west coast of New Zealand is a remote and empty place!

The next town to catch our interest was Hokitika, which according to Joy's guidebook would be a good place to browse craft shops. As predicted we found lots of jade carving studios and jewelry stores and shops selling various woodcrafts and wool, but they were all about to close and we only made it to a few places. It was late in the afternoon and we needed to be moving on anyway to find a place to stay in Franz Joseph. Joy was getting anxious about not having a place to stay on a Saturday in a popular town; I on the other hand was excited about the coming thrill of hunting down a suitable room at the last minute. As we drove farther south the clouds lifted, revealing nearby snowy peaks behind fields of grazing sheep. This was the quintessential New Zealand I'd dreamed of: ice soaring high above rugged forested slopes with flat fertile fields down below where sheep nuzzle tufts of tender grass.

Franz Joseph is a quaint little alpine town ten miles from a lovely ocean beach and one or two miles from the melting edge of a glacier. Its rugged setting and proximity to snow fields, raging rivers, and dramatic scenery have made it a mecca for young travelers like ourselves though I found the offers a bit beyond my interest. Dozens of tour operators, restaurants, bars, and hostels court visitors with drink coupons, free movies, and the temptation of helicopter flights directly to the snowfields and Mount Cook. It's the sort of place where one can linger for weeks in a cheap hostel room, sharing a kitchen and bath with ten or twenty like-minded youth from various parts of Europe, Australia, and the US, going out for drinks in the evenings or chatting with friends in the hostel lounge. We were just staying one night and chose to keep to ourselves, walking up as close as we could to the Franz Joseph glacier at sundown and then retiring to a counter at a pizza cafe where windows looked out at the vista of icy peaks and steep ridges. We watched the sky turn purple and munched on hot pizza and cold beer. There's a wonderfully dark Montith's Black brew from Greymouth; it was just the thing to finish off a long day of driving.

Through the night wood smoke from an adjacent building, part of the hostel with "ski lodge" written on a decorative sign over the door, wafted in through crevices in the window. The smell was comforting. Stars appeared in the sky some time after sunset but later they faded as clouds moved in and a steady cold rain began to fall. This continued into the morning. It was the sort of morning you would want to start with hot chocolate and toasted muffins so that's exactly what we did, lingering near the electric heater that every room seems to be furnished with in New Zealand along with fluorescent lamps and impractically small plastic washbasins - to name a few things I found odd. The washbasins were too small to wash one's hands or face over without splashing water everywhere, they were flimsy plastic, and separate hot and cold faucets made it impossible to get warm water to wash with: only scalding or freezing water was available. Kiwis should consider properly sized porcelain sinks, mixing faucets, forced water heating systems, and less harsh lighting options.

We drove to Fox Glacier next and walked up to its base where jagged toothy spires of melting ice fed the swollen meltwater stream. Red lichens covered the rocks like at Franz Joseph but there were no kea birds, inquisitive green mountain-dwelling parrots that we'd seen the day before at the base of the glacier. Fox Glacier is in a wider valley and the town feels less like a mountain hamlet and more like a highway stop with sprawling hotels and a main street you could drive through without slowing down. We wanted to see mountain views from Gillespie Beach, a driftwood-strewn gray beach twenty minutes west over a slow gravel road, but with low clouds hanging overhead and light rain there were no mountains to be seen. The beach with its heavy surf and abundance of twisted bleached tree trunks and stumps looked eerily like a wrecked beach head where a great army had come ashore under heavy fire and swept inland leaving a trail of debris.

Gray weather also muted the mountain vista that would have been reflected on the shining surface of Lake Matheson, which we didn't even walk over to. We just ate lunch at the adjacent cafe which was completely overrun with people from a tour bus. Pumpkin soup and a sandwich warmed me up thought the crowded cafe wasn't quite the sort of place where I could relax while sipping hot soup and gazing out the window at distant sheep. To me, the glacier towns seemed contrived and I felt pressed to take on an unnatural fascination with the mountains or the sports to linger there. Everything was brought from far away; we hadn't seen any sort of economic industry for hundreds of miles and there had been no cell phone service since Nelson. Settlements on the west coast might only exist because against lurking suspicions to the contrary, the people have convinced themselves that their towns are real.

I was interested in finding a place to stay the night that was firmly rooted in reality. As we drove south, things seemed to be improving in this direction: the landscape got more wild and rugged and there were no towns at all. Along the way we walked 30 minutes from a gravel roadside lot to Munroe Beach, stepping carefully around mossy puddles that ran through the wettest and most jungle-like forest of rimu trees and giant ferns we'd seen yet. Moss and vines were draped over streams tinted orange by deep mats of fallen leaves. Heavy surf pounded the beach. We looked for penguins but saw none, which wasn't surprising since it was midday and the yellow crested penguins were out fishing or else in their burrows keeping eggs or chicks warm. Black flies followed us in clouds when we stopped. I scavenged among the stones long enough to find a weathered chunk of what looked like green jade, not of high quality due to pockets of softer rock and variations in color but very attractive because of its glassy smoothness. It started to rain then so we walked back to the car, happy that it was just a passing shower.

There was only one town where we might stay the night: Haast, the last outpost on the main road south before the road turned inland through the central mountain range. A stiff wind sent ripples through fields of grass along the road and the sun was shining through broken clouds when we pulled up to a general store - the only one in town - to buy canned peas and beets and pasta for dinner. A motel was attached so we asked to see a room. Our hostess acted like this was a chore and showed no entuhsiasm for anything until we agreed to take the $85 room which came with a hot plate, electric fryer, sink, and a rather inconvenient and small bathroom that reminded me of an airplane lavatory. "Don't bother me in the morning; just leave the key in the door when you leave," she said after we'd handed over some cash and made small talk about the wind.

After filling up the car's gas tank we set out on a 45-minute drive south to the very last outpost on the west coast road, the village of Jackson. With just a few buildings and an aging wooden pier there wasn't much to look at besides some informational kiosks and a rainbow shimmering above surprisingly blue water. We kept watch for penguins on the way back, even stopping at a small beach to look around, but while there were no penguins to be seen I discovered that in this distant corner of the planet hardly any seashell-gathering beach walkers came past and consequently there was a vast undiscovered trove of beautiful shells to be picked up and heaped in the back seat of our car. Black flies chased after me in swarms and it was raining lightly so the experience wasn't exactly ideal (Joy stayed in the car) but I did gather a sizeable collection of shells before conceding that I had enough.

Clouds were lifting from the adjacent mountains, revealing fresh snow on the higher slopes. We stopped again at a bird sanctuary and estuary where boardwalks meandered through the quiet waterways and signs taught us about the plants and animals that lived there. On the other side of the roadway was the beach and every so often we passed a dirt track leading out to it. I took one, steering the car over the packed sand to a clearing in the shrubbery looking out over a huge empty expanse of sand beaten by foaming surf and lit orange by the light of the setting sun on broken clouds to the west.

Water boiled exuberantly on the electric hotplate and light from incandescent bulbs radiated warmth from the pink walls of our room. Darkness had fallen and the heavy curtains were drawn tightly closed. Joy neatly laid out bowls and poured glasses of sauvignon blanc she'd bought in Marlborough, positioning them on the dilapidated formica card table beside the freshly opened cans of cold sliced beets and green peas while I fixed macaroni and cheese. A tiny television in the corner only received a few static-smudged channels. I felt like we had arrived at the edge of the world, a place lashed to the rest of civilization by two tenuous strands of roadway and a rotting wooden pier thirty miles south where great waves swept in from iceberg-ridden waters off Antarctica carrying seashells and twisted timbers torn from the shores of Fjordland and Tasmania. There were no pretend adventures or mock ski lodges here and it didn't feel like anything was about to change for the better or worse. There will always be cans of green peas (packed in Australia from New Zealand ingredients - why?) and waves crashing beyond the grassy dunes and a broken bathroom door in the motel room. It was simply peaceful.

We had to leave far too soon. Alarms woke us after a short night's sleep; our evening and stretched until midnight but there was oatmeal to eat with bananas and tea and the adjacent beach had to be searched, at my insistence, for seashells. Unfortunately the fortuitous currents that had delivered expired gastropods to the sandy shore near Jackson did not have the same effect farther north. Lines of waves marched eastward and spilled their energy in frothy swaths against a flat pebbled slab of earth and red-legged black gulls stepped confidently among rivulets of water paying no attention to me as I collected colorful pebbles and then tossed them back once they dried to dull crumbs of rock. Eventually we were on our way into the mountains passing cyclists embarking on what must be a lovely though strenuous ride alongside a blue mountain stream where red-flowered Rata trees bloomed and fresh snow dusted slopes not far away. Sunlight streamed through broken clouds and a steady flow of motorcycles and cars descended from the mountains as we drove higher. The day's first visitors from Queenstown and Wanaka, most of them would pass right through Haast with hardly a glance at its handful of buildings.

Along the way we stopped to see several waterfalls and deep river pools filled with water so blue it seemed almost unnatural. Water is after all faintly blue in color so when there are no impurities or silt or algae to scatter light and the deep stream bottom is scoured rock only the blue color reflects back to our eyes. The road never did reach the snow, sneaking over a pass and dropping immediately to large green pastures flanked by tall craggy peaks perpetually covered with ice. The landscape was at once settled and domestic, its wild character subdued by neat fences and well-built homes. There were several stunning overlooks above Lake Hawea, a large blue basin surrounded by green mountains and flowering shrubs, and more bordering neighboring Lake Wanaka (the name rhymes with Monica).

The town of Wanaka sprawls across the eastern end of the lake. An immense green lawn with what must be the skateboard park with the best view in the world dominates the waterfront and an adjacent downtown area sports restaurants, shops, bars, and hostels. Yellow, white, and purple lupines dotted the shoreline which was partolled by flotillas of ducks. Gentle waves washed against a line of driftwood and people walking dogs or riding bicycles passed on a nearby path. We found a room with ensuite for $65 at the Purple Cow, a fantastic little hostel with a huge common kitchen, a big-screen tv room, and a restaurant-like seating area with booths and tables set against a window wall looking out over the balcony and lake vista. At the grocery store we bought venison cutlets (along the roadway we'de been eyeing deer grazing in pens blissfully unaware of our intentions) and potatoes and onions and mushrooms. I bought some yarn at a wool store and we got postcards and browsed at the lakeside Information Center. To avoid the dinner crowds we cooked our meal a little early and enjoyed the savory morsels at a corner table looking out over the lake, then went out for a walk. With the solstice approaching darkness didn't fall until around 9pm.

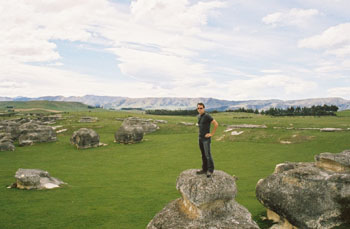

The road east through Oamarama and Kurow took us past great fields of purple and white lupines, crowded along riverbanks like colorful carpets. The higher passes reminded me of Bolivia with their tufted golden grasses and a backdrop of red desert hills streaked with melting snow. I stopped the car frequently and dashed out with my camera, vaulting over fences and sneaking up on unsuspecting tufts of grass to capture the lovely scenery. Once in my eagerness I glanced up at the sun to see whether a cloud was about to move and got an eyeful of direct sun. It hurt for a while after, a reminder that the ozone layer is very thin down South. We fed a hungry sheep juicy green grass from beyond its pen behind a craft store along the way and walked among elephant-shaped boulders on a windy hilltop somewhere west of Oamaru where sheep had cropped the grass so it looked like a carefully manicured lawn in the middle of nowhere. Layers of domed clouds lurked over mountain ridges as if concealing alien spaceships, not moving with the wind, towering high into the sky with tiers like a Japanese pagoda. The wind blasted across the hills with violent strength. A bit farther on, there were houses and towns and suddenly the sea appeared.

Unlike the wild blue western waves, the surf at Moeraki was subdued and brown. The tide was out, revealing giant spheres of rock strewn around on the beach: these were the famous Moeraki Boulders, unusually large concretions huddled in clusters like turtles. Some had cracked open to reveal cores of rusty orange crystals. A steady stream of people walked across the flat sand beach from the car park three hundred meters distant, looking like pilgrims crossing the desert to a holy site. It was mid-afternoon so having revised our plans to ride horses in the central rangeland we struck out for Dunedin (pronounced DUN-ih-din), the big Scottish city in the south draped over a hilly harbour.

It had been a long day. The car was safely parked, our bags were stacked at the side of a tiny room hardly larger than the bed, we had finished off a tasty meal of sushi and soup at a Japanese restaurant, I'd checked my voicemail and found no messages from work and a voicemail from Steve wondering why I wasn't around the day after Thanksgiving (sorry guys - home for Christmas this year), and at last we were seated at a wooden picnic table outside on our hostel's rooftop balcony over a pool hall eating a big Venetti ice cream cake. This heavenly creation of layered gourmet vanilla ice cream and flaky thin dark chocolate was immense and slowly melting as we attacked it with our forks while the last light of the day faded from the pastured hills surrounding the city. When the last dollop of sugary goodness had been put safely in my stomach we retired to our room, drew the thick curtains as best we could to cover the entire wall of glass facing the main outdoor corridor, and went to sleep.

Most of the hostel guests rose early and hurried outside to board buses that would take them on prescription tours of Southern New Zealand. I much preferred our meandering car trip and at about $US500 for sixteen days of car and fuel it sure seemed like the better deal for the two of us. The aging Toyota Corolla had been doing very well and we'd heard not a single complaint from under the hood. Joy made toast and we drank tea and relaxed for a while before setting out to explore the Otago Peninsula, a windy spit of land inhabited by albatross and penguins.

The albatross colony at Dunedin is said to be the only "mainland" colony in the world. The birds circle the globe at its southern end each year, soaring on their huge wings with the prevailing winds. Their wings fold in three sections rather than the usual two and they have a distinctive silhouette; we saw some at dusk above the blustery headland where they have their nests. We went there for lunch at the visitor center but opted not to take the somewhat expensive guided tour of the nesting area on the cliffs. Instead we walked out to the beach and looked for penguins and saw honeycomb-like columns of basalt just like the Devil's Postpile at Mammoth Lakes in California or the Giant's Causeway in Ireland. clusters of yellow lupines were blooming along the sand dunes but the yellow-crested penguins we hoped to see must have been out at sea hunting for fish.

Returning to our hostel I decided to drive the high road along the crest of the peninsula. A narrow road led along steep grassy hillsides dotted with sheep and stunning views of the sea and rugged hills surrounded us on all sides. At a bend in the road I spotted a wooden sign for Clifton Wool 'n Things. We drove past, but I thought better and turned the car around and steered it down a rough rocky driveway flanked by heavy walls of stacked fieldstone. At the end of the driveway was a farmhouse with several weathered barns; one had a sign by the door that said "ring the bell and I'll come up from the house." As it turned out, the proprietor Ian was already there in the wool shop having just received some other customers. I could hardly believe my good fortune when I opened the door and stepped inside: it was a wool store, the real thing, the authentic New Zealand sheep barn I'd been searching for.

I collect blankets when I travel. They are functional and durable and every one says so much about the place it came from, by the colors and patterns and materials and weaving styles. I have a brown alpaca saddle blanket from Bolivia and a red wool shukka from Kenya and handspun silk from western China and a stack of other things and I absolutely needed to bring home a weaving from this misty hillside in southern New Zealand. Sheep of many colors grazed outside and their fleeces, ranging in color from dark chocolate through coffee and caramel to oatmeal and cottony white, were spilling out of bags, carded into rolls, spun into great bundles of yarn, and knitted or woven into all sorts of blankets, sweaters, hats, and scarves. Not a single dyed scrap of yarn was anywhere to be seen. I loved it!

Old farm equipment was hung from the rafters, not for show it seemed but just because the wool shop was set up in an old barn. Prize ribbons from local fairs hung on the wall beside letters from schoolchildren. Outside, Andy the young black sheep raised his head to be scratched behind the ears and trotted around in circles like an eager puppy. I felt like I was in paradise. We browsed through the stacks of blankets and left with an armful, then returned the next morning and bought more things including an immense fluffy brown sheepskin that I occasionally try to pass off as a bear skin to unsuspecting houseguests. My duffel bag swelled with the great quantity of yarn and wool I'd accumulated, even after I'd wrapped bundles tightly with paper and rope.

In the evening after dinner we waited with a small group of people huddled under nylon jackets and knit hats at the gravel lot beside Pilot Beach where we'd heard that blue penguins would come ashore at dusk. Two penguin-counting volunteers were there with clipboards and orange vests. Right on time at quarter past nine the first batch arrived, appearing suddenly in the small waves and waddling up the beach and past us to burrows in the hillside. These miniature animals, the smallest species of penguin, can get around quite well despite having two very short legs positioned in a way very inconvenient for walking. They swim with their flippers and evidently their feet are specialized for burrowing but I still don't see how an unstable flippered bird can make a tunnel in firm clay without some soft of tools or mechanized equipment. It was raining and cold so after several waves of penguins had arrived we returned to our cozy accommodation beside the harbour: a vintage 1940s Bedford Bus!

Rain battered the metal roof, gusts of wind pried at the doors, and surges of water washed down the windows. Joy pulled the hand-sewn curtains across the windows and I rummaged around in our bags by the light of a single lamp that was wired back to the main house with an extension cord. The bus was surprisingly spacious, painted neatly in cream and forest green, fitted with a coal stove and a metal sink that wasn't connected and a closet, some cabinets, and a table with bench seats for two. Up front there was room for a driver and passenger and in the back a full-sized bed with a rustic wood headboard rested comfortably against the wall with windows all around. In faint light outside I could see the dark lake close by and steep, hilly pasture land all around. Except for the rain and occasional solitary cars pushing through the darkness on the road outside everything was still. Our bus felt safe and warm and cozy and I wanted to stay there forever under the heavy blankets listening to the rain pattering on the roof.

There was one problem: I had to pee in the middle of the night and it was still raining and the house was dark and distant. Fortunately, it was raining and dark and there were bushes about. Visit the Bus Stop Backpackers yourself if you're in Dunedin, and ask for a rainy day in the bus or maybe try the caravan trailer out in the back yard.

Snow had dusted inland hills with a white frosting overnight. The road north was wet and intermittent squalls spat cold raindrops at the windshield. We didn't stop at Moeraki, pushing on instead to Oamaru to make it in time for lunch at the Whitestone Cheese Factory. A platter of tasty cheeses was laid before us, brie and blue and cheddar and some local creations made from sheep's milk or dairy. Our sandwiches were excellent as well. Afterward we strolled through a viewing area inside the small factory, peering through misty glass into concrete-floored rooms filled with metal racks of moldy cheese rounds or big stainless steel vats for mixing or rows of cheese presses. I hadn't ever thought much about how cheese is made: it's rather simple. Curdle milk with cultures, stir, press, age, and eat. We bought some cheese to eat later and drove a couple blocks to our hostel.

Oamaru has a lovely old section of town where nearly every building is built from local limestone. There must also be coal deposits in the area, because the pungent familiar odor of burning coal wafted out of stovepipes. Workmen on break chatted at the front of an ironworking shop and across the street men worked in a wool warehouse where big wrapped bales of wool sat ready for shipment. It was chilly and raining lightly so we stepped into a bookstore. Inside the air was intensely warm, heated by a coal fired pot-bellied stove in the middle of the room. Black lumps of coal glistened in the bottom of the coal box next to a basket with split kindling for starting the fire. A stern-looking older woman dressed in a gray suit stood behind a counter. A blackboard behind her listed coffee and pastries for sale. Russian music was playing; it had a patriotic sort of energy to it that along with the warmth of the coal stove and the shelves of books left me feeling numb with satisfaction. I wanted to stay and browse books all afternoon.

Next door we stepped into a bookbinder's studio. Book binding by the methods used by monks for centuries is almost a lost art, but there in Oamaru one can still buy an authentic leather bound book with blank pages ready for recording the wonders of the world. Joy bought a small album-type book; it would make a good scrapbook. Outside it was raining again as we walked back to our room at the bed & breakfast.

It was getting late in the afternoon, near penguin time, so we drove to a clifftop overlook on the coast where yellow-eyed penguins come ashore. A steady rain was lashing at the coast and no penguins were around so we returned to town, bought some groceries, and fixed a quick dinner before driving back to the penguin lookout. This time there were penguins! Eight or ten of them came ashore one or two at a time, swimming like ducks until they got to shallow water whereupon they stood up and waddled with surprising speed up hidden paths through the grass and shrubs to burrows high above on the hillsides. Only slightly put off by our presence, they marched right past us watching us with looks of disinterest in their pale yellow eyes and paused on hummocks of grass to preen their feathers. Yellow-eyed penguins are two and a half times larger than the little blue penguins we'd seen the night before. When we left, a newborn lamb not more than a few days old was frolicking by the roadside with its mother. I got a fantastic photograph as we passed.

Darkness was fast approaching so we hurried to the Blue Penguin Sanctuary adjacent to our Bed & Breakfast. Joy had bought us tickets to a special penguin nest tour and viewing from a pavilion that seats about fifty people. We peered into dimly lit burrows from inside a specially built shed (penguins are actually somewhat of a pest, being loud and obnoxious and awfully smelly, and they will nest in any suitable enclosed space such as the provided nest boxes). It was nesting season and some rotund gray chicks huddled in their burrows waiting for mom or dad to return from the sea with dinner. The parents alternate burrow duty and fishing, swapping every day or two and returning in the evening. Evidently the birds hunt alone most of the day but gather offshore at dusk and come in together in several groups for extra protection from the dogs, cats, weasels, and other predators on land.

I was disappointed that photography was strictly phohibited, even before darkness fell, because as the sun sank behind the hills an absolutely stunning rainbow appeared just offshore over the water. It was the first time I'd actually seen the end of a rainbow; it plunged into the water in a mist of shimmering colorful droplets. A faint second band of color appeared alongside the first and golden rays of sunlight lit rocks at the end of the jetty as if they were molten metal. Offshore, dramatic clouds turned purple and orange and dark bands of rain fell into the sea. Our host talked about penguins and then pointed out some rafts of birds waiting far offshore. One came in early in full daylight, the tiny birds quacking incessantly and scampering directly to their respective burrows. Darkness soon fell and more birds came ashore, perhaps a hundred and fifty of them in total, and suddenly the shrubbery came alive. Alarming shreaks and squawks reverberated off the cliffs. Tuxedoed youngsters beat their wings and stretched skyward, proclaiming their strength and trying to woo identical tuxedoed females and chasing them around at reckless speeds. Every so often I'd notice another shadowy white form emerging to a clearing in the trees, pausing as if to survey the crowd and then stepping up to the podium to proclaim sovereignty over the land.

After a while fuzzy round chicks energed from their burrows and began chasing their parents around trying to get food. The chicks actually grow larger than their parents at the fluffy gray stage before they mature to sleek blue-backed birds that have no idea how to swim or fish. Once fully grown, they venture out on their own to learn the ways of the world but not all are successful. We saw several lone birds going against the flow, hobbling down the rocky shore to the water and diving in to go fishing at night!

Back at the room our host Roland had delivered fresh baked bread made to our specification: whole wheat, with sesame seeds, warm and wrapped in a towel. It was delicious with cheese from Whitestone. We finished it off in the morning before setting out on the final drive to Christchurch where we would spend our last two nights. It was sad and a little frightening to be returning to a big city after two weeks of traipsing around remote countryside; even Dunedin had been compact and rural feeling outside the city center. Christchurch on the other hand was flat and sprawling. For lunch at our hostel I cooked up the last soup meal I'd packed for the hike in Abel Tasman. Afterward, we went to an animal park where all sorts of farm animals and New Zealand birds roamed in open pens. our mission was to see the rare nocturnal kiwi bird and we eventually located one sleeping in a dark building (evidently they aren't entirely nocturnal). we stopped by again later and found it awake and snuffeling through dry leaves with its long beak.

The park was criscrossed by pathways and nearly every animal was waiting eagerly to see us. We'd bought a paper bag of pellet feed at the entrance and though it was sold as wild bird food, it looked like the farm animal food they were selling and the deer, ducks, pigs, donkeys, sheep, goats, and lots of other animals all liked it equally well. I learned that an ostrich has a bite like a jackhammer and a thousand pound clydesdale is as gentle as can be. I rescued a little duckling that had become separated from its mother by a low wire mesh fence. Once restored to the company of its friends, it took to the water and zoomed around with the other ducklings like a supercharged racing boat, gobbling up green water plants and leaving a vee-shaped wake. The adult ducks were preoccupied with begging for food and weren't nearly as cute.

We slept in the next morning. It was the first time we weren't going to be moving to a new place, but we did eventually get our things together and drive an hour through beautiful green hills to the old French settlement of Akaroa on the Banks Peninsula. Surrounded by green hills and brilliant blue water, the pastel colored town is lovely. After a lunch of steamed green mussels that, while tasty, couldn't possibly compare to the ones we ate at Pipi's Restaurant in Kaikoura, we spent our last twenty-five dollars on a one hour kayak rental and two ice cream cones. We paddled around the harbor looking for wildlife, finding gulls and geese. We had wanted to paddle in Dunedin where we might have seen penguins and seals and sea lions but the weather was too windy there. After returning to shore we sat out on a pier and raced to eat our ice cream faster than it was melting.

That's where it ended - the ice cream disappeared, I drove us back to Christchurch, we packed our bags and left extra supplies in the share bin at the hostel, and in the morning we dropped off the car and got a lift to the airport. Twelve hours of flying took us home, Joy to San Francisco and I to Los Angeles. I know that back in New Zealand the green grass eventually turned brown in the heat of summer and the wildflower-filled fields went to seed and faded and the frolicking little lambs grew up and turned into old slow moving sheep, but I still can't imagine it that way. As far as I'm concerned, New Zealand is always a fairy land with crystal blue water, golden sandy beaches, tree ferns and elephant shaped rocks and fields of lupines, rivers of ice and soaring granite peaks, vineyards and breweries and huge pots of steamed clams, empty black pebble beaches, and millions of adorable little sheep.